RIDGE ART REVIEW

ESSAYS

Le Repas Frugal | by Emmet Elliott | January 6, 2026

Perception and the Essay of Criticism | by Eric Bayless-Hall | December 15, 2025

Alla Prima Amnesia: Phoebe Helander at P·P·O·W | by Anna Gregor | December 15, 2025

Homage To— | by Arnold Klein | December 15, 2025

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Ridge Art Review is an art / criticism magazine founded on the conviction that individual artworks are the basic unit of meaning in art analysis, that perception is an activity and takes work, hence that writing criticism is its own creative work.

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Le Repas Frugal

January 6, 2026 | by Emmet Elliott

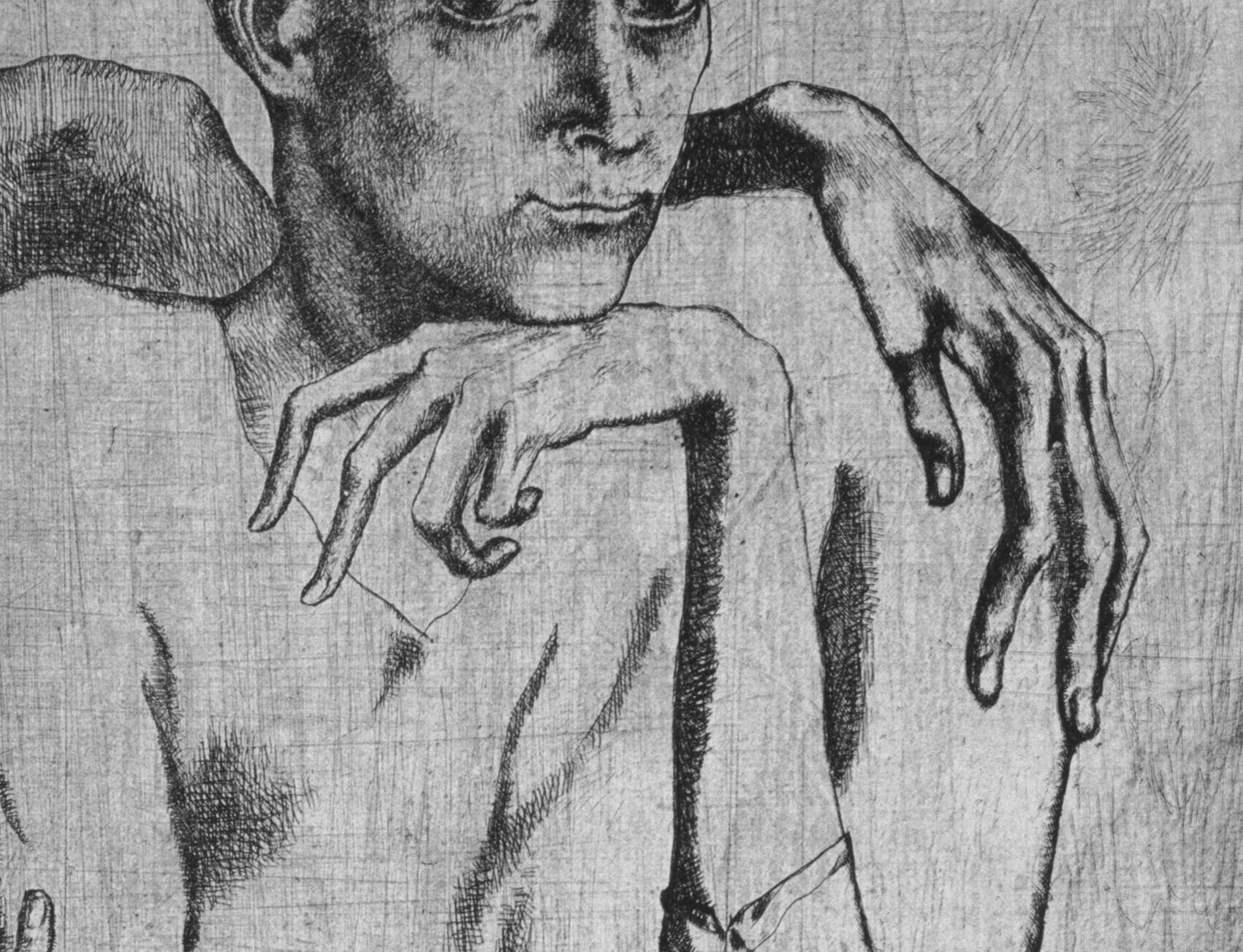

Pablo Picasso, Le Repas Frugal, 1904, printed 1913. Etching, 25 11/16 x 19 11/16 inches (sheet), 18 1/4 x 14 7/8 inches (plate).

The plate has been polished clean. The bottle has been almost emptied. In this etching, completed by a 22 year-old Pablo Picasso in 1904—his second print ever—we find a terrifyingly hungry young man.The plate itself was inherited from another artist, and would have had to be polished before etching could begin. If the faint thicket above the woman’s head is any indication, Picasso was eager to put this stage of the process behind him. The traces of bushes, as well as of grass and stones along the left, show us that the plate had been a landscape before Picasso turned it 90 degrees, and into the haunting portrait of an impoverished couple.Yet it is not simply a portrait. Picasso also borrows another genre from his tutor Cézanne—the still-life—to amplify poverty by foregrounding what is not there: more bread, for example, food on the plate, or knife and spoon. The plate looks to have been wiped clean, probably by the missing half of bread, and eaten with the hands. But whose hands? Maybe only one of them is ravenous. After all, her face is rendered with prominent cheekbones, yes, but it is not, as his, emaciated. There is still bread in front of her, her glass is half full, and perhaps most notably, her mouth is not open, not searching for the next morsel, but pursed. No, they are not hungry—he is hungry.But why should we associate the man who would go on to become the most prolific artist of the 20th century with the man in the etching? Is it because of his left hand, which emerges floatingly to the right of his companion’s face, drawing her into mid-air with impossibly long, articulate fingers (her left shoulder will be the final stroke)? Is it because the man seems to be missing his eyes? Because his eyes cannot be shown looking to the left of the frame while at the same time looking at the whole of the frame, gazing from the same position as ours? Does their absence from the picture—all the more conspicuous for their contrast with her vacant stare—call attention to their presence in front of it? And is it because we have seen Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, done only three years later, and know that the theme of the gaze, of looking at women with a jarring eroticism, would come to be a central aspect of Picasso’s work?Perhaps. But just as Demoiselles, this piece escapes simple reductions. There is just too much to see: the mysterious shadow behind the man which echoes the soon-to-be-empty bottle; the tablecloth (or is it paper?), which could almost be a cubist painting from ten years in the future, and repeats itself around and rhymes with the man’s neck; the subtle (and not so subtle) allusions to death, catholicism and even the printing process itself: an ink bottle, plate, and sponge all placed on a sheet of white paper. We can see Picasso musing on poverty, on death, on drunkenness, on printmaking and maybe even on what lays ahead of him… but the violence of desire, as much as we might wish otherwise, is as unavoidable for us as it was for him. Picasso keeps bringing us back to those four hands—which build an echo of the etching plate at its center—and what they frame. They frame the object of a young man’s desires, the source of his insatiable hunger in the stark black and white of ink on paper.

Detail.

About the Author:

Emmet Elliott studies, practices, and writes about architecture, urbanism, and the visual arts.

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Perception and the Essay of Criticism

December 15, 2025 | by Eric Bayless-Hall

Dewey was right about one thing, at least. Seeing (or hearing, etc.) a work of art one is not merely passive. Just as the artist’s work wasn’t pure activity, but was, instead, punctuated by periods of seeing what’s just been done, so the viewer is not merely receiving the work in front of her, but engaged in actively recreating it: coming to see the connections between points or marks or themes or thoughts that the work of art is made of. We don’t need to buy a philosopher’s first principles and last conclusions to borrow the wisdom that washes up between them. And ordinary Dewey is wiser than most—enough to see a distinction worth making for all your gold: recognition is not perception.Forget, for once and for a while, your pet theory of recognition, and consider the sense this makes: we recognize what we know well enough for a purpose; whereas we begin to perceive when we haven’t yet finished learning what we’re looking at.Recognition is, on this view, a toolbox of types by which we fit a manifold world into familiar forms—classify quickly threats and objects of desire and the means to avoid and pursue them. We recognize, roughly, the things we have easy words for—this or that as this or that sort of thing; a pear, a panther, a painting, Paul Newman. However we came to see the world in the first place, the fact is, we find ourselves here, having started, and our seeing of things is always and irreducibly a seeing-cum-understanding—that is, we recognize more or less when we look. But the miracle of perception is—and it is, indeed, a miracle, for it seems, not only unexplained, but unexplainable without begging the question—that looking with attention actually discovers more than it originally recognized. That we recognize the world is remarkable; that it continues to reveal itself to attention is more remarkable still. This discovery of what’s in front of you by means of attention is what Dewey calls perception, and that it takes the form of modifying what we first thought we saw is what he means in saying recognition, though it is not yet perception, is the beginning of perception.Perceiving is a name for the work of seeing something unique, something that cannot be classed without sacrificing something of its distinctive character. Looking—really looking—which is as much an activity of the mind as the eye—reveals, remarkable as it continues to sound, this thing we’re attending to to be more and often other than we thought at first blush. Our initial recognition is developed, by an activity involving language as originally as color, into a more intimate familiarity with this particular thing. The more one looks, the more peculiar the thing under inspection becomes; and the more peculiarities one comes to find definitive of what this thing is, the more one will insist on the insufficiency of what we’re calling recognition: that you have to see, really see it.Whatever else we come to view as particulars—people, for instance, and the things we love—works of art can almost be defined as those human products whose particularity we insist on in our meaningful dealings with one another. Recognition doesn’t begin to account for our interest in them; nothing said about a work will be relevant until it springs from (what we’re calling here) perception.With these notions in hand it should be needless to say that the critic of art ought to perceive the work they write about—really see it. It will be equally obvious, however, that much of what passes for criticism is but the rehearsal of what is recognized. Critics, if there are any, are hardly more insightful on the whole than the tourist eager to announce before his tour guide tells him that that, in fact, is a Rothko they’re approaching. If you’ve had one Rothko pointed out to you, you can recognize them all as belonging to this type; but this patron, like the critic who associates in front of a painting without discovering these connections in the work under consideration, exhibits the perceptive powers of the man who catcalls legs from his car. What has actually been seen?And why is anyone supposed to care? Why write—and why read—art criticism that doesn’t do the work, first, of seeing what it’s pointing to, and second, of communicating it coherently? Here I’ll just report a hypothesis I’ve harbored for some time and say: serious looking will express itself in serious writing. My proof? The pudding. Try conveying a perception (in our sense here) in easy words and see if you don’t find yourself walking a thin ridge between the stodgy and the inane. Slipping into either you will know yourself to betray the sense you hope to express. If perception requires work, then this goes doubly for the writing of what’s perceived. One wonders how critics, supposedly devoted to the power of art, forget when they face the page that they face a form of the same problem as the artist.Now these two requirements, as I see them, for a critic—that they work really to see what they criticize and that they work really to write it—grow out of the basic nature of the undertaking: writing about works one’s encountered; and says about this undertaking only: strive to do it well or not at all. It should not be taken to deny, however, that writing about art well can take many forms, nor that critics, like artists, like humans, fall short on occasion. It is to say, rather, that criticism is to be an essay of one’s sense: an attempt to convey the reality one perceives as one perceives it, and this will involve criticizing oneself and one’s sense as much as the work one’s work is about.

About the Author:

Eric Bayless-Hall teaches and studies in New York. His writing appears in The Revenant Quarterly.

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Alla Prima Amnesia

Phoebe Helander’s Paintings from the Orange Room at P·P·O·W

December 15, 2025 | by Anna Gregor

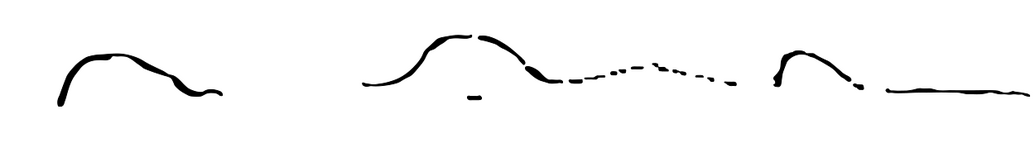

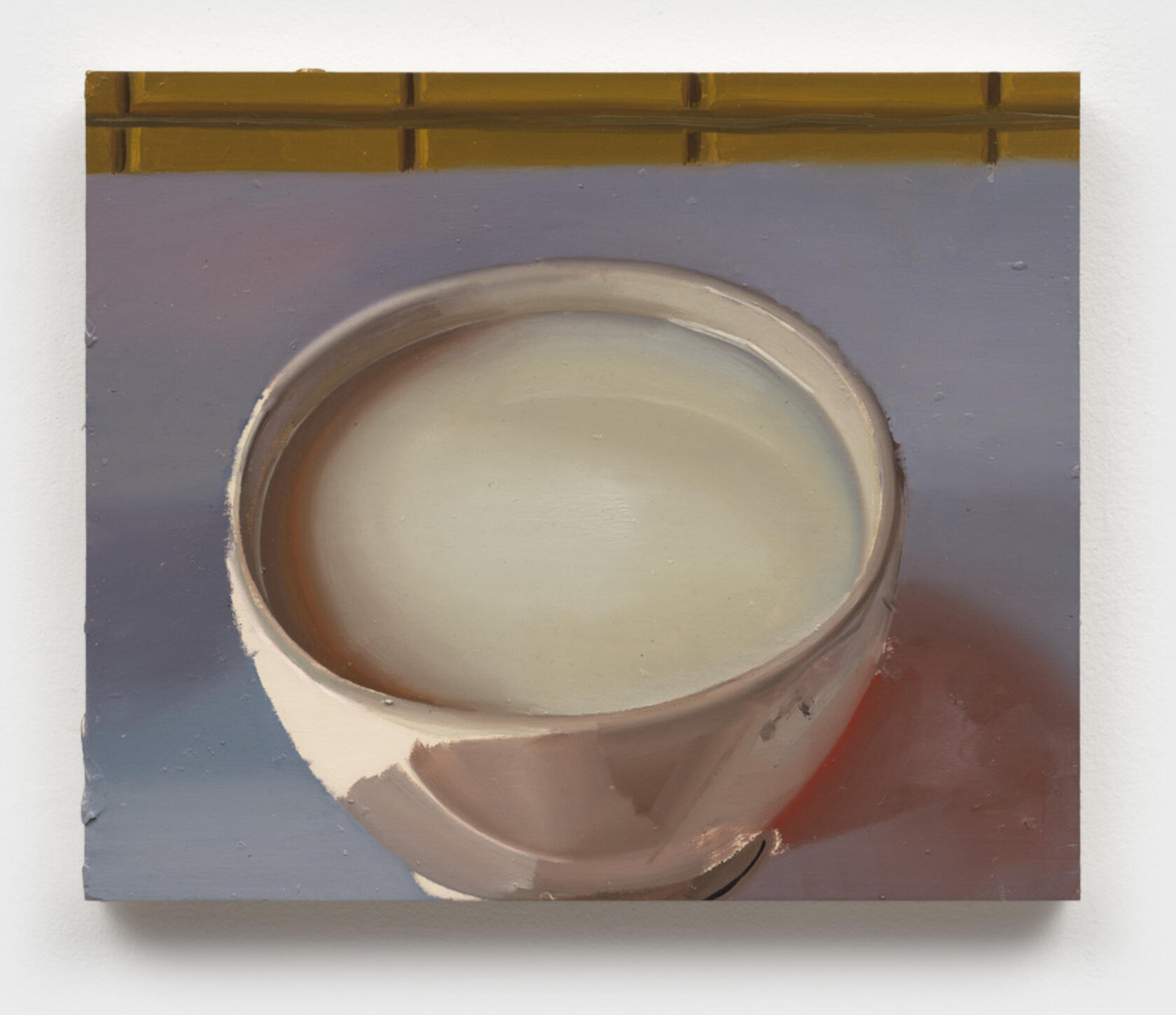

Phoebe Helander, Bowl of Milk III, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 1/2 inches.

There must be over fifty paintings in Phoebe Helander’s Paintings from the Orange Room at P·P·O·W. All are still lifes, approximately head-sized. Most are painted on uncradled slabs of wood, some of which have already begun to warp or split. The panels appear to be prepared hastily and en masse, their edges splintered and striped with drips of gesso.The paintings are nice, even refreshing, compared to the other painting shows on view in the area. The lack of preciousness evident in the panel preparation contrasts with the careful representations of familiar still-life objects while accentuating the materiality of the painted images. In the best of the paintings, material support, brushstroke, and represented object correspond, synthesizing present and re-presented objects (painting and still-life subject). In these works, the close-looking of observational painting is materialized, asking for and rewarding the same type of close-looking on the viewer’s part. The white lines separating the segments of a lemon echo the drips of primer down the sides of the wood slab. A crack in the wood panel creeps across the representation of a fallen red glass, as if the cup’s fragile surface too threatened to split. The wrinkled surface of unevenly dried paint acknowledges the passage of time while representing a momentary quiver in a bowl of milk.

Phoebe Helander, Cross-Section of an Old Lemon II, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 inches.

This synthesis, however, happens in only a few of the paintings in the show. The many others land in the comfortable realm of alla prima still life—fine enough (for decoration). But the paintings claim to do more (or, rather, their maker claims they do in the show’s accompanying essay and press release): to bear witness to change and instability in a world that quantifies, sensationalizes, and advertises. But although painted in front of wilting bouquets and burning candles, flower and flame alike may well have been painted from photograph, so stable and unproblematic are Helander’s finished paintings. There is nothing inherently wrong with paintings that take on the quality of photographs. But we do not see like cameras. And Helander’s commitment to durational six- to ten-hour alla prima painting sessions of changing objects, to perception beyond the screen, more often than not results in photographic images, so that the process is only discoverable in her writing (by turning our attention away from the works to read an explanation of them):“So I end up continually painting over my work, re-making the same central area of the composition, for as long as the candle burns. Loss is a natural part of change, and that’s something I accept as a part of this work. My goal is to stay with the flame.”A nice idea. But paintings are ideas materialized. And the idea is not materialized in most paintings in the show.Paintings are static, visual objects. To materialize loss, a painting must contain what was before—it must reveal its own history visually. Such a commitment to durational attention as Helander’s, if it is to become art and not simply a token of her personal meditation (for what could we viewers learn from the latter?), must solve the formal problem of how to embody the phenomenological experience of an object that is three-dimensional and temporal by nature in the two-dimensional and static medium of paint. This problem was not solved, once and for all, with Cubism, or Futurism, or any other Modern -ism. It remains the problem of each painting today. How do we represent the world when we are habituated (addicted) to having screens and algorithms pre-process experience for us?Contrary to Helander’s “staying with the flame,” the kind of attention that is the antidote to the doomscrolling, ad-riddled, ADHD-inducing addiction of contemporary life is not the mere presentness of sense certainty, for which this-here-now is all there is and is gone as soon as it is. Such is the ahistorical presentness of the amnesiac. A productive presence of mind would rather be a type of attention that brings its past forward with it: a presentness with a historical consciousness that is aware that the material it encounters is informed by what happened before—whether the wax formations of a melting candle, a prior brushstroke by one’s own hand, or the historical genre of still-life painting—and is the ground from which the future develops. The real problem is how to cultivate presence of mind while committing to what came before and what comes after: a problem that painting alla prima may not be able to tackle with its limit of working only while the paint is wet. What happens when Helander commits to the same painting day after day? Month after month? The solution would perhaps not be so fresh, so nice, so many (so potentially profitable). I venture to think that such an undertaking might be appealing to Helander, given the values she articulates in her essay and her attraction to materials that change over time (pools of medium-rich paint that will wrinkle as they dry, warping supports that will crack the paint film).That most of Helander’s paintings don’t go beyond a way of seeing habituated to a pre-processed, flattened image taken by a mechanized cyclopic lens, is understandable given the nature of her undertaking. The formal-material problem she has set herself, which requires overcoming deep conventions of how we see today, is vast enough to devote a life to. The three or four paintings in the show that hint at a solution to the problem are promising steps for further inquiry. That the show at large doesn’t go beyond an Instagram-like glut of images, turning the three room gallery space into a kind of feed in which the viewer circumambulates instead of scrolling through images packed too close to each other, however, undercuts the project. The painter’s commitment to this problem would be more convincing had the forty-six or -seven other paintings been left out. The success of this project would entail that each painting asks a viewer to look at it with the same degree of effort and attention that was put into it—an impossible task in a space packed with fifty paintings and nowhere to sit.

Phoebe Helander, Cross-Section of an Old Lemon II, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 inches.

Phoebe Helander, Paintings from the Orange Room, P·P·O·W, 390 Broadway, 2nd Floor, October 31 - December 20, 2025About the Author:

Anna Gregor is a painter who occasionally writes about Paintings. Her essays can be read in The Revenant Quarterly, Caesura, and Two Coats of Paint.

RIDGE ART REVIEW

TITLE

ARTIST/EXHIBITION

DATE | by AUTHOR

ARTIST, TITLE, YEAR. MEDIUM, DIMENSIONS inches.

BODY TEXT

ARTIST, TITLE, YEAR. MEDIUM, DIMENSIONS inches.

ARTIST, EXHIBITION TITLE, GALLERY, ADDRESS, DATE.About the Author:

AUTHOR BLURB

Website

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Homage To—

December 15, 2025 | by Arnold Klein

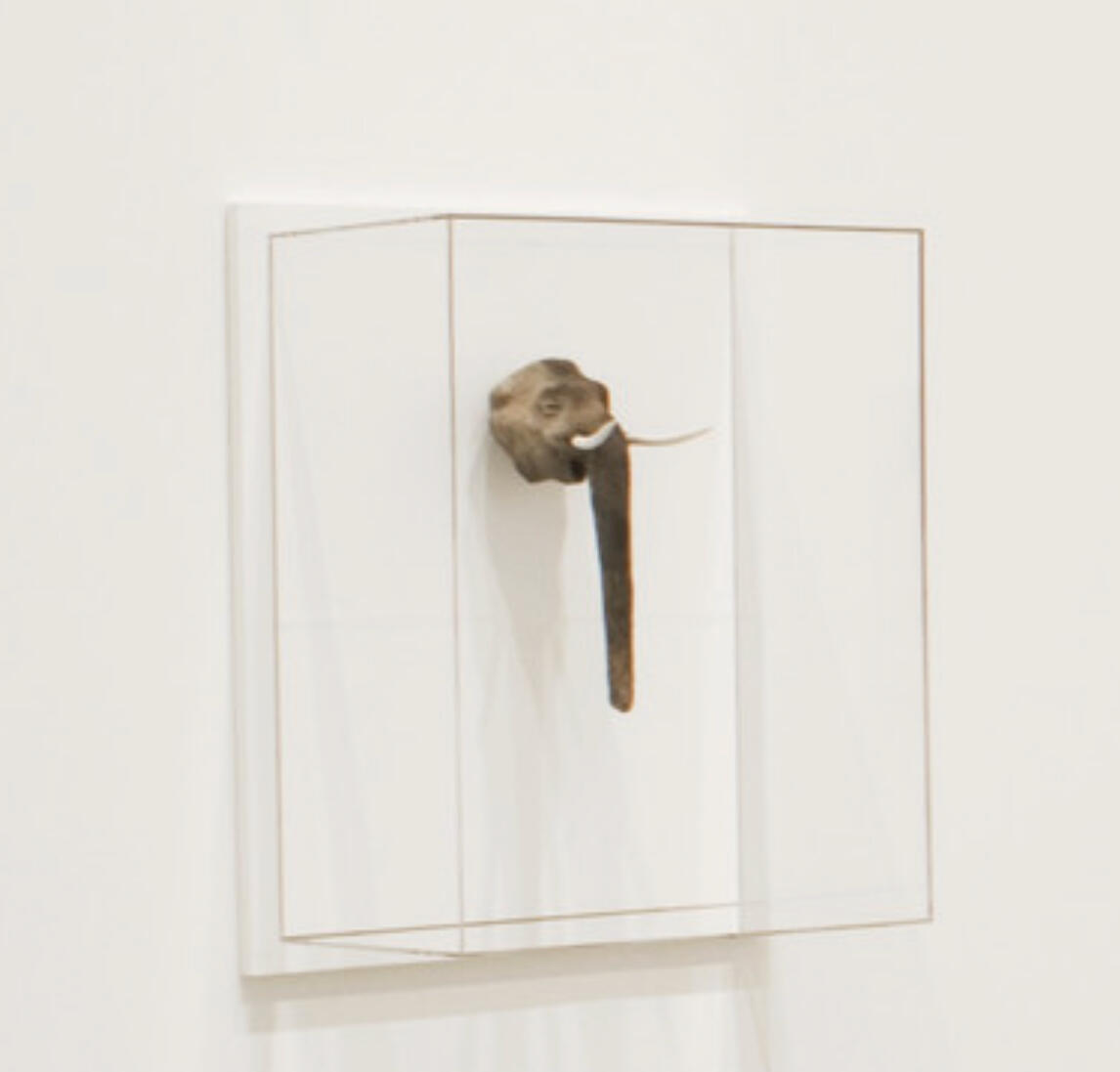

Peter Fuller somewhere recounts how his unconversion from what may be called the Acrid School of Marxist Art Criticism was effected by his encounter with an ancient sculpted head, whose power to move him he found wholly unrelated to the class struggle, means of production, false consciousness, late capitalism and all the rest.Well, I had a similar experience—though not of unconversion from an ideology but of confirmation to what I take to be a cardinal artistic value—up at the MOMA a few years ago when I turned the corner of a room containing the perfectly awful portrait of Condeleezza Rice by Luc Tuymans (and I name it, her and him for a reason) and came across—But before getting to exactly what I came across, let me say of the experience itself that it was characterized by the absence of what I usually find present in my visits to the art world and by the presence of what I usually find woefully absent there.What was absent in that experience that was usually present? Discourse: discourse contextual, biographical, art-historical, critical even, overt or implied; and all the cants respectively accompanying them—the whole logo-noetical sea into which, as Gilson says, everything disappears. (The Talmud is not wrong when it reminds us that the tongue is the only muscle that never gets tired.)What was present, that was usually absent—that obviated discourse, and rendered it impertinent in both senses—malapert in both senses?Imaginative expression.Expression has gotten a bad rap; it has been taken to mean something like unclarified and uncontrolled emotion. But I mean it as referring, in art, to any significant record of a sensory-motor-affective-intellectual experience, including, of course, the (sensory-motor-affective-intellectual) experience of coming to clarify that experience in a material form, that is, in a work; and I call it “imaginative” because it is only in some power that is neither sense, motor, feeling nor intellect only that those (and everything else coming into it) can form a unity and result simultaneously in a record of that unity, that is, in a work. I don’t mean to commit myself to a facultative theory of mind here, only to emphasize that, in expression, the whole person is at once the impetus and the site of a process, whose termination, in art, is a work.As must the whole person be engaged, in the reception of a work.Not the “effect:” effect implies passivity on the part of what is usually called the reader, the viewer, the audience, and so on; the-eye-goes-here-the-eye-goes-there sort of thing; the we-laughed-we-cried sort of thing; the what-did-the-poem-make-you-feel sort of thing. But reception is not passive—you make yourself receptive, you engage (in Captain Picard’s sense) what Pater called “the power of being deeply moved,” as paradoxical, even as oxymoronic as these formulations sound. Not every work put out as art, or putting itself out as such, calls for reception in this sense, the discourse-laden portrait of Rice certainly does not;—or answers your call, though more works than you might think will gladly do so, if asked (but not until then). As Lamb said of certain old books, and as we might say of certain cold people, some art works have to be loved before they will prove themselves worthy of love.So imaginative expression covers both sides, maker and recipient, as the recipient is remaking the expression of which the made thing is the significant record, from that record alone. You can call it communication if you want to, if you emphasize the commune part, the verbal stem, not the petrifying -ation, the noun, and even abstract noun, part, as two whole persons are indeed meeting; but not if you regard communication on the usual verbal model of one-party-telling-something-to-the-other, simply, and disregard the plain fact that the other in even the simplest case must take the words in, which is another way of saying make herself receptive, if communication is to take place at all. And not if you assume, again on the usual verbal model, that communication is always about something (the what-is-she-trying-to-tell-us sort of thing; the what-is-this-movie-really-about sort of thing), as there is no about in communion.So what was the work that confirmed my commitment to imaginative expression as a cardinal artistic value?You see my dilemma: no discourse allowed! But before I name it, and the name attached to it on the museum plaque, let me say something about this sad business of associating art works with the empirical persons usually taken to be their makers—the people who are born, live and die, eventually becoming fodder for biographers—instead of with I will call, following Croce, the aesthetic personage, knowable to us only through, and as, the physiognomy of the works themselves.As to the empirical person: it is not merely that most of the world’s greatest works are anonymous, actually anonymous; it is not merely that the materials for anybody’s life are fragmentary and variously interpretable, when in fact there are any such materials left (as there are not in Shakespeare’s case, among others); it is not merely that most of anybody’s life, and probably the most important part—the moment-to-moment contents of her consciousness—leaves no record, variously interpretable or otherwise; it is not merely that biography is a literary genre and no more to be credited as true than any other subclass of fiction, including history, nor that it follows pseudo-absolute interpretative fads (who swallows “psychobiography” anymore?); it is not merely, in sum, that people are unknowable, even to journalists. It is that the empirical person and the aesthetic personage are of completely different interests.A Nietzsche scholar quoted by Rorty (I don’t have the book to hand) says he is not interested in “the miserable little man who wrote Nietzsche’s books,” but in the character created in them; and here too, I am not interested in the by-all-accounts wonderful empirical person named on the plaque, but in the aesthetic physiognomy projected in the individually characteristic works that go about in the world under her name. Let’s get the order straight: the empirical person, even if we knew anything more than a few promiscuous superficialities about him or her, which we cannot (see above), would be of no interest whatsoever but for its misleading association with the artistic personage and its physiognomy, which we can know so profoundly.1And I might add, know directly. The empirical artist may be sheltering in Rossinière or drinking in Soho or moldering in Vauvenagues Castle or currently dust, but the works are right here, silently calling to us or silently waiting for our call to answer.But here’s the thing: not every work going by an artist’s name will originate in the aesthetic personage and manifest its characteristic physiognomy. The empirical person can still use a paintbrush, and other interests than purely artistic, i.e., imaginatively expressive, ones (rhetorical ones, for example) may direct her hand. Such works will go by the same name as the artistic ones, of course, and sell out of the same dealership and take up space in the same museum, though one would hope an expert institution like the MOMA could discriminate between the two, between what Croce called poesia e non poesia, between painting and not-painting, and not devote wall space to canvasses that have nothing expressive going for them beyond their nominal association with an artist, Luc Tuymans, and his subject, Condeleezza Rice, say.Once upon a time, at Fanelli’s, around one p.m., it was not uncommon for the conversation around not a few tables to turn to the question of “who was the greatest living painter,” and the debate (to date it somewhat) usually devolved into a contest between Balthus and Bacon and sometimes Mitchell, although one of the participants (initials R.L.) always and quite sincerely named himself. Well, convinced as I was that afternoon that whoever made Elephant with White Tusks was our greatest living artist (and no, I haven’t seen everything by everybody—but neither had the Fanelli’s painters, and that didn’t stop them), I set about trying to find other works by the same maker, and here knowing her name was very useful in hunting up a few images and a catalogue; but the one at the MOMA remains the only sculpture that I have seen in person.But at the risk of saying something, not so much about that sculpture as about why you should be interested in it: its chief expressive qualities are compassion and fragility; not compassion for fragility, for the fragility in question includes the compassionator no less than it does the piteous animal embodied in its burnt clay, and, indeed, through that, includes us all, human and animal—since all of us are, like clay, a little earth and a little water, fused for a little while by the fire of vital heat.I have a feeling that this, or something not far from this, is the physiognomic truth of the works that are going about in the world under the name of Daisy Youngblood.

1 And ditto for such curatorial concerns as “The Roots of Fauvism,” “Pioneers of Abstraction” and so on—we would have no interest whatsoever in the inchoate but for the perfections alleged to have developed from it. Matthew Arnold got it right when he warned that the “historical estimate of art” would divert attention to origins and away from the consummations that alone would give them such interest as they might possess. (For a lark, try searching "pioneers" in the MOMA database.)

Daisy Youngblood, Elephant with Tusks, 1995. Low fire clay and paint, 18 1/4 x 14 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches.

About the Author:

Arnold Klein's work appears regularly in The Revenant Quarterly.

RIDGE ART REVIEW

Virtuosic(-ish) and Vacuous: John Singer Sargent and Doron Langberg | by Candice T. Seymour | December 13, 2025

Langberg, Doron

Virtuosic(-ish) and Vacuous: John Singer Sargent and Doron Langberg | by Candice T. Seymour | December 13, 2025

Sargent, John Singer

Virtuosic(-ish) and Vacuous: John Singer Sargent and Doron Langberg | by Candice T. Seymour | December 13, 2025

Seymour, Candice T.

Virtuosic(-ish) and Vacuous: John Singer Sargent and Doron Langberg | by Candice T. Seymour | December 13, 2025

Virtuousic(-ish) and Vacuous

John Singer Sargent and Doron Langberg

December 13, 2025 | by Candice T. Seymour

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882. Oil on canvas, 87 3/8 × 87 5/8 inches.

There is something off-putting about the paintings of John Singer Sargent. Mention him to a painter and they're certain to remark on his virtuosic paint handling, the luminosity of his lights, his ability to capture his sitter’s countenance… But they are just as certain to, in their next breath, mumble something about not caring very much for his work. A noteworthy admittance, given that painters are generally suckers for “painterliness” (particularly in an age, like ours, when a decades-long dearth of technical skill has boomeranged into material fetishism). This is not to suggest that professional paint pushers are right in their judgments of paintings (usually they are not), but it is a convenient fact for this author who, after visiting the Metropolitan’s recent Sargent in Paris exhibition, was convinced of the paintings’ utter vacuity—and this despite Sargent’s apparent “virtuosity.”It is difficult to put one’s finger on what’s off. There is something a little lechy in Sargent’s gaze, not unlike the attention paid to girls by their older cousins: icky but probably not dangerous. But this is not enough to make a painting bad. There are many creepier, infinitely better paintings by Balthus. There is something tasteless in the displays of wealth in his depictions of his bourgeois clientele. But Velasquez’s paintings of kings and aristocrats retain their profundity, which suggests that the ostentation alone can't be the cause. Most interestingly, there is something that reminds one of images generated by AI, something beyond the performative brushiness of a digital paintbrush. One is tempted to claim: Sargent’s paintings lack soul. But (though right) such an articulation is not productive for criticism. The “soul” they lack is not that of the empirical person, John Singer Sargent, nor that of his sitters. (Lest we forget, misled by biopics and wall plaques, the empirical people behind a work are irrelevant to it.) The paintings themselves lack a soul, that special animation of an artwork that defines itself.

John Singer Sargent, Staircase in Capri, 1878. Oil on canvas, 32 × 18 inches.

They are soulless because Sargent was unfaithful to them, though his wayward desire was not for his sitters, but for their money. Doubtless, his clients patronised him because of his manual skills, best exemplified in Staircase in Capri, where the lilting brushstrokes transform the flat rectangle of the toned linen into the deep space of a rising staircase, as if by magic. They must have drooled over his ability to transform raw paint into depiction and, money in hand, commanded, “Make me such a thing!” And so he, rather than treating each painting as a problem to be solved, the solutions of which, concurrant with its form, would have been its very significance; rather than finding a new problem for each painting of each sitter, Sargent reached for a canned problem: the generic problem of luscious paint becoming represented thing. As in the portrait of Marie Buloz Pailleron, he’d sketch in a cloying background behind his subject, within which he would paint a flower over here, a flower over there, then—voila!—a glob of paint next to them, as if to say, “Look at the magic of paint! Look at the virtuosity of John Singer Sargent!” Canned problem, unreal solution. Hence, the emptiness that recalls images generated by Dall-e. In the paintings in which he seems to have tried for something deeper, as in The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, he gropes for significance on the wrong plane: that of symbolic meaning, the kind of meaning that Adorno calls thematic, which goes extinct with time as conventions change. Baby girl with a baby doll, young girl, pre-teen girls, giant vases prefiguring the rounded shape of pregnancy: one can get no further with this painting than the empty idea of motherhood looming over the girls’ futures. Only what is more than merely thematic content persists, and already, a mere 150 years later, this painting is substance-less. What appeared as virtuosic fades into cliché.This brings us to Doron Langberg’s Lovers at Night, just a few galleries and a flight of stairs away. The painting of the lovers, like Sargent’s paintings, pretends to the problem of paint becoming depiction. Also like Sargent’s paintings, it at first appears virtuosic(-ish). But the painting of the two lying figures, composed of performative brushstrokes with neon underpainting peeping through, their bodies nearly dissolved into abstraction, reveals itself to be substanceless. Its rhetorical meaning is clear: the act of painting (playing with variously-colored, luscious liquids and semi-solids) is analogous to the acts of eros undertaken in bed by lovers. In acts of love, two bodies dissolve into one; in art, the viewer, likewise, loses themselves in pleasure by luxuriating in the materiality of the painting. Art, like love, is hedonistic: pleasure, like art, is the highest achievement of humankind. This would all be well and good if the painting achieved this, but it remains on the plane of thematic content, mere syllogism rather than significant solution to a problem in paint. Although the paint that composes and surrounds the two lovers at first appears luscious, the closer one looks, the more contrived the image, the more stingy the paint’s application, the more performative the brushstrokes. Less does it seem that the figures came to be at once with the whirlwind of paint manipulation, more does it seem an academic sketch of figures, stylistically unfinished because the artist, much like the average adolescent pencil-wielder, doesn’t want to labor over digits or members. Allegedly a homoerotic encounter, only one of the figures is identifiably male, so even the “subversive” content is undefined, present in word only. Like the verdict on Sargent’s works, one might say that this thematic content has perished with age. But since the painting was made less than two years ago, it’s more likely that it was empty the day it was made.

Doron Langberg, Lovers at Night, 2023. Oil on linen, 80 x 96 inches.

About the Author:

Candice T. Seymour loves good artworks, is tired of mediocrity, suspects most artists don’t even like art, and hates nihilistic “critics”.

Substack

RIDGE ART REVIEW

ARTISTS

Helander, Phoebe

Alla Prima Amnesia: Phoebe Helander at P·P·O·W | by Anna Gregor | December 13, 2025

Picasso, Pablo

Le Repas Frugal | by Emmet Elliott | January 6, 2026

Youngblood, Daisy

Homage To— | by Arnold Klein | December 13, 2025

RIDGE ART REVIEW

SUBMISSION REQUIREMENTS

Reviews / essays can be submitted for consideration using our Submissions Form.Submit all other inquiries below.

CONTACT

Please send us a note if you want to be added to our mailing list.